Articles & Excerpts

Please note that most articles in the Resource Section are either exact or revised excerpts from Corinne Levitt: Exceptional Minds Across the Autism Spectrum.

▸ “See the person not the label” (Temple Grandin)

The Lessons from the past have much to teach us

After four decades of teaching as a special educator, it is curious that I now find myself advocating on behalf of my students with ASD and/or developmental differences in much the same way I did back in the 1970s for my students with learning disabilities. During that time, I’ve witnessed the important and successful shifts that have happened in the three decades since students first introduced learning disabilities and learning differently to our educational system. Individualized education plans were just being developed at the time, and now they are common practice.

The good news is that the learning disabilities legacy has taught us important lessons about people who learn differently. Differentiated instruction is now widely practiced. Teacher training now focuses on understanding dynamic differentiated learning styles; developing inclusive learning communities and bullying awareness is a common goal for education today.

Yet “special” education is still considered separate and apart and has not been wholly integrated into the educational psyche; there is still that sense of otherness, rather than of just being different, particularly for non-verbal and highly anxious students with ASD or students with physical challenges. We tend to underestimate students who may appear to be underachievers when in fact nothing could be further from the truth.

We are now challenged with to extend what we already know to every unique mind as we rise to the challenge of providing meaningful educational opportunities for all exceptional students across the autism spectrum. It is time to raise our expectations, stretch students and teachers beyond their comfort zones, identify student strengths, and encourage them to develop to their full potential. What holds us back is our difficulty in changing our perception of those who appear different. We are the ones who must change our behaviour and recognize our students’ strengths and capabilities.

Our new task is to change our current mindset. Just as we rose to the challenge back in the 1970s, so too can we begin to extend our deep understanding of those who learn differently to all students.

Anthony: A Student Teaches Us a Valuable Lesson

Anthony was a fourteen-year-old Grade 9 student who would soon help his high school teachers re-examine their preconceived ideas about hidden abilities and educational “standards.” When Anthony first arrived at his new school, in the late 1970s, his teachers saw a student who was struggling with his courses, failing history and English, and receiving special education resource room support for a few hours each week. They noticed he rarely made eye contact, was physically and socially awkward, had sensory issues with respect to noise, was reluctant to speak in class, and had difficulty writing things down and staying on task, with a tendency toward hyperactivity. His teachers questioned whether he was ready for high school and wondered if he should have been held back in Grade 8 for another year, for it was believed that an academic high school was not the appropriate place to learn the basics or receive remedial support.

Anthony’s parents reported that he seemed more comfortable in the company of adults than with his own peers, and as a child had spoken late and was physically awkward. But they noticed that, around the age of four, he suddenly made up for his language delay and showed remarkable strength in the areas of reading and verbal expression, despite his ongoing difficulty demonstrating these abilities in writing. As well, Anthony had many hobbies, including assembling stereo equipment from commercial kits, and a love of music.

It wasn’t until adolescence, at the insistence of his parents, that Anthony received his first formal psychoeducational assessment from the school board, in order to determine which high school program would best meet his needs. The report indicated that Anthony had a previously unidentified learning disability and above-average intelligence, even though he had experienced much failure throughout elementary and middle school and barely passed Grade 8. In spite of this new information and the diagnosis identifying Anthony’s high level of intelligence, his parents still wondered if an academic high school was appropriate, as his uneven learning profile presented something of a paradox. (Looking back, I recognize that Anthony had that “little professor” air about him, a term Asperger had used in his seminal paper on the syndrome later named after him. But of course, we didn’t yet know about Asperger’s work.)

Nevertheless, the term learning disability would serve Anthony’s needs quite well. Anthony was given access to the special education resource room where we could address his learning needs in conjunction with his courses of study. During our sessions there, I encouraged Anthony to focus on his verbal strengths, to dictate his answers into a tape recorder in a quiet and private setting where he could relax and also transcribe his thoughts and ideas into written form, thereby demonstrating his true abilities to his teachers. (Anthony’s writing was almost illegible, so he typed his work whenever possible. Those were the days of typewriters and White-Out; today, computer programs like Dragon Dictate work quite well in this regard.)

One day, Anthony’s history teacher came to see me, showing me his latest assignment. Rather than being pleased with his progress, she appeared quite upset; she believed Anthony had cheated in light of the poor quality of his previous handwritten assignments and his reticence to speak in class. She couldn’t understand how he could possibly be capable of producing this high-calibre work, given his difficulty with basic skills. I played Anthony’s tape for her and she was impressed by what she heard. Could this be the same student? What magic had I performed? But there was no magic—I had just given Anthony the opportunity to demonstrate his abilities and let his strengths shine through.

A two-dollar cassette tape, an old typewriter, and a change in mindset helped redirect Anthony’s educational path toward university and success. His teacher’s new ability to see his strengths instead of his deficits helped her understand him and his previously hidden abilities. The experience also helped her question her preconceived views about learning disabilities, learning styles, and intelligence.

Anthony’s teacher became a strong ally and suggested that I speak at the next staff meeting to help other teachers understand more about different styles of learning and the implications for teaching. From that day forward, Anthony was able to further not only his own education but the education of his teachers as well.

A Shift in Mindset

An amazing educational transformation began to take place in our schools, beyond what we could possibly have imagined at the time. And it was all because our students with learning disabilities, like Anthony, responded so well to this new, neurologically informed approach to teaching and learning. Our students’ progress exceeded our expectations and taught us an important lesson about the value to be found in different ways of thinking and experiencing the world. Educators and researchers took notice and began to move away from the limited view of simply addressing deficits, taking a deeper look into the thinking patterns and perceptual abilities of these interesting and capable students. They wondered if their success might have important implications with respect to current teaching approaches for all students.

The experience taught us that understanding neurological challenges serves to broaden our teaching abilities—and our ability to enhance the learning potential of everyone—as we continue in our efforts to explore and learn more about the inner workings of the human brain. And I believe that this understanding, and the neurologically informed approach to teaching, opens up even more possibilities for students on the spectrum.

As I continued working as a high school special education resource teacher throughout the 1980s, the demand for effective teaching approaches and better teacher training continued to transform our understanding of the word exceptional: exceptional was no longer the exception, but instead the rule for best practices in teaching for all students. I continued to broaden my experience and understanding by taking advantage of new teaching opportunities that were now being offered in a variety of settings.

Toward the end of the 1990s, as the number of students with ASD was steadily increasing, so were the challenges facing well-meaning educators, challenges not unlike what we experienced when students with learning disabilities first made us question many of our preconceived ideas about deficits, abilities, intelligence, and different kinds of minds.

As I began working with my students on the spectrum, I recognized a growing need to improve educational opportunities for students who learned differently but were often still misunderstood. And I began to realize how helpful my background in learning disabilities would be as I embraced this new and important educational opportunity.

As I continued to observe various programs and approaches for students on the spectrum, regardless of the setting or school level, I was surprised to discover that a greater emphasis was often being placed on students’ deficits and what they couldn’t do, rather than on their strengths. This ran contrary to what the previous few decades had taught us about the neurological nature of different styles of learning; somehow, this understanding did not seem to include students on the spectrum. How easily we forget the lessons from the past when facing yet another new and unfamiliar challenge in education! But I held fast to what I knew to be true, knowing that my background in learning disabilities and strength-based teaching was exactly what my students needed.

During the last few decades, we public school educators have witnessed a sea change in our understanding of the learning process, and have come to realize that a neurologically based view of different thinking patterns and learning styles is so effective that it is no longer limited to students with learning disabilities—but now is considered to be the gold standard of instruction for all students. “Differentiated instruction,” also known as “universal design,”, based on an appreciation of varied and diverse patterns of thinking, has now replaced the one-size-fits-all teaching methods of the past. So why hasn’t this understanding been extended to students on the spectrum, who also learn differently? Like learning disabilities, ASD is recognized as a neurological condition, so why is the neurologically informed approach not being used with students who stand to benefit the most from these techniques and practices?

Exceptional Minds provides a powerful new way of thinking about the autism spectrum and education, to see past student deficits and recognize the potential to learn and thrive. Readers meet students like Tally, whose obsession with pulling at threads and scratching her skin was redirected when she learned how to knit, discovering both a hidden talent and an opportunity to sell her handiwork. And there is Eric, who developed his skill for poetry, and was thrilled when his poem was published in a prestigious public library magazine. The students and their experiences challenge all of us to re-examine what lies behind our current understanding of the autism spectrum and learning differences, in order to create a school culture based on dignity, respect, social inclusion, and the right to a meaningful education.

▸ “Ain’t Misbehavin’”

Life is full of surprises. When I first started teaching students with developmental needs, including many with autism spectrum characteristics, I discovered that my students and I were in fact more alike than different. This was contrary to what I had been taught as part of my teacher training, where “different” and “special” were emphasized, while sameness or commonality were not even considered relevant. However, as I came to know and understand my students, I realized that their behavioural characteristics represented many aspects of most people’s personalities writ large—characteristics and traits that we (neurotypicals) had learned to control and keep in check, lest we offend. Yes, people with ASD may have difficulty controlling certain behaviours, but we all possess these characteristics and desires in varying degrees.

In the groundbreaking book Animals Make Us Human: Creating the Best Life for Animals (2010), Temple Grandin, along with co-author Catherine Johnson, offers helpful advice for pet owners, farmers, livestock handlers, and even zookeepers. Yet, as the title reflects, Grandin’s insights have far-reaching implications for human behaviour as well. Her findings not only made me aware of the misperceptions and misunderstandings I had about our family cat, they also helped me realize and appreciate how much our environment impacts both animal and human behaviour, and how changes to that environment can elicit more positive outcomes for all of us.

It is Grandin’s expertise in the study of animal behaviour and her unique and, yes, empathic understanding of how much the environment helps shape animal and human responses that has enriched our understanding of ASD at such a profound level. But now we must take that understanding to the classroom so that its influence can be realized each and every day in the lives of our students.

Grandin helped me develop a new understanding of behaviour, and I soon realized that I would need to look at behaviour, the environment, and teaching a little differently. I would need to figure out not just what was wrong but, more importantly, why it was wrong in order to design an effective and meaningful classroom learning environment for my students. Many of these changes are easy to implement and are based on common sense; the challenge, however, is getting professionals to think about the why together with the what.

As educators, we must now understand the importance of facilitating changes in a student’s environment in order to address the causes of concerning behaviours. There is still a tendency to focus on changing the child rather than addressingthe sensory and perceptual challenges that impact the child within their environment; we must keep reminding ourselves that the behaviours are more a consequence of the environment than simply a feature of ASD. The chicken-and-egg dynamic can sometimes cloud our ability to tease cause from effect, but Grandin’s research demonstrates clearly where the true problems exist; we need to look at the outside world and its influence on the child’s responses, with our focus resting not solely on the child but rather on the many influences that can shape responses and behaviours. When square pegs are able to fit nicely into round holes that have been broadened and modified, there is much less friction and far less wear and tear on the pegs.

Hakim: “Noises Off”

Temple Grandin (2010, 3) wrote, “My theory is that the environment animals live in should activate their positive emotions as much as possible, and not activate their negative emotions more than necessary. If we get the animal’s emotions right, we will have fewer problem behaviors.” This statement can apply equally to the classroom environment.

A normally calm and quiet student of mine, Hakim, became agitated when our classroom was disrupted by support staff who wanted to use the laundry facilities in a connected room. Not only did this intrusion interrupt our class, but we were also subjected to the unpredictable sound of the dryer’s BUZZZZZZZ!!!!!! as it reached the end of the cycle. The jarring sound upset the entire class, but it created a particularly high level of anxiety and upset for Hakim. He loved music and had perfect pitch, and seemed especially sensitive to annoying sounds, such as chairs scraping across a tiled floor. We placed tennis balls on the legs of our chairs, which easily solved that problem. The dryer problem, on the other hand, presented more of a challenge.

I had tried to arrange for access to the laundry room to occur outside of class hours, but to no avail. My request was not taken seriously, as clean kitchen towels were needed for the school cafeteria. Hakim’s problem was not considered to be that serious; his reaction was viewed as typical autistic behaviour. It was suggested that perhaps Hakim could simply wear headphones when the laundry facilities were in use. I explained that headphones weren’t appropriate for this situation, as we were all bothered by the noise and disruption, but I was told that many Individual Education Plans recommend the use of headphones for students with sound sensitivities, and this situation was no different. Hakim was sixteen and had never used headphones before, and I worried that introducing headphones at this stage of his life might actually heighten his sensitivity and create more problems in the long run. He’d managed quite well until the dryer situation had presented itself. Hakim’s response to the buzzer was actually quite understandable.

I too was annoyed by the dryer’s jarring buzzer. It often frayed my nerves and disrupted my own train of thought. More importantly, it interfered with our learning, and with the positive classroom environment I worked hard to establish.

Once that buzzer went off, our learning potential for the rest of the day was compromised.

When I was teaching Grade 12 English in a traditional high school, my class would never have been interrupted by support staff carrying out laundry duties. It is simply not done. Was the teaching in my class with special needs students of any less value? Did people believe our job was more caretaking than helping students learn and find their place in society before they must leave, at the age of twenty-one? There was important learning taking place and much work to be done. The situation was unacceptable, as was the attitude that went with it. Too often, special education programs are reactive rather than proactive, with a tendency to respond to situations only when they become problematic. In the long run, this ends up creating more problems than it solves. We must take full advantage of the time our students spend in school to honour their right to an education. Parents fought long and hard to achieve universal access for students with disabilities, which means access to a proper education and not merely access to the building.

When the support staff arrived with their baskets of laundry, long before we even heard the sound of the dreaded buzzer, Hakim would begin to show signs of distress, immediately getting out of his chair and pacing back and forth at the back of the classroom. It was clear that he was no longer able to focus on his schoolwork, and this was unacceptable to me as his teacher.

Since I had rejected headphones as the solution to this problem, I realized I would have to find a creative solution on my own. So, with the help of another staff member and a handy Robertson screwdriver, the buzzer was silenced forever. Peace and quiet was finally restored to our classroom, and Hakim was able to continue with his schoolwork. Unfortunately, I was less successful in preventing the disruptive interruptions from the support staff. Change doesn’t always come as quickly as we would like. While I was able to find a partial solution by silencing the buzzer, I realized that we faced a far more serious problem with respect to heightening awareness about the sensory issues that can and do compromise the learning environment for students with ASD. And there is an even greater need to raise awareness about the value of education in the lives of our students.

While headphones can be effective in certain situations, they should be used with care and common sense. When overused, they can further isolate students and limit opportunities for social interaction and meaningful communication, the very things we wish to encourage. Our goal should be to use such strategies less and less as we help our students adapt to their surroundings. But first we must recognize the cause of the problem and consider how much the environment impacts student learning. Misdirected solutions that focus solely on “behaviour” may work in the short term, but end up creating more problems, as well as limiting rather than enhancing learning potential. We all need to adapt if a change for the better is to be realized.

As Temple Grandin reminds us in her first book, Emergence: Labeled Autistic (2005, 146), “The principle is to work with the animal’s behavior instead of against it. I think the same principle applies to autistic children—work with them instead of against them. Discover their hidden talents and develop them.”

Hakim graduated a few years later and found a part-time job at Tim Hortons. With the help of a supportive and understanding employer, he is happy and successful. He loves listening to the music in the background and often sings along while he works.

▸ Flexibility and Schedules – the ISH Lesson

Too Much of a Good Thing

Children on the spectrum are encouraged from an early age to follow written/icon schedules to allow for easy transitions. I completely agree with this strategy—when it works, it’s great. But when life’s unpredictable events interfere and disrupt our plans, disaster and meltdowns often follow. Working with schedules and learning how to adapt when things change will help students develop transition skills as they navigate the detours of daily life.

Ellen: It’s about Time

Ellen was very good at following clear instructions and schedules. She remembered everyone’s birthday. Her father affectionately referred to her as his personal assistant and “human Blackberry,” regularly reminding him about his upcoming dental appointments, hockey games, wedding anniversaries, and other important events—for which he was most grateful.

Ellen loved schedules. Schedules make a chaotic and unpredictable world more manageable and provide a sense of control. But of course it is just that, a sense of control, as real control is not possible. So what can we do to prepare our students for days that don’t run like clockwork?

One day, after visiting her eye doctor, Ellen handed me a note indicating that she needed to be given eye drops every day at noon for the next two weeks. The eye drops were kept in the main office and would be administered by one of the educational assistants at lunchtime.

The next day, as our class got ready for lunch, the noon bell rang and Ellen immediately began to pace. She started to panic and screamed, “It is twelve o’clock—eye drops—the doctor said!” Then she began to repeat the doctor’s instructions, “Ellen must have eye drops at noon…” Unfortunately, the educational assistant was delivering medications to other students and hadn’t yet arrived. I called the office to get the assistant to come directly to our class, as nothing else would calm Ellen. When she finally received her drops, she settled down but was completely worn out for the rest of the day.

This was not the first time that a change or delay in a schedule had resulted in a student having a meltdown. The recovery and the effect on the student and other members of the class could disrupt the entire school day and have a negative impact on the learning environment in the classroom.

I realized that for Ellen, noon meant 12:00 sharp. She remembered the doctor’s exact words and, with her tendency to rely on the literal, took the word “must” at face value, believing that something catastrophic might happen if the doctor’s exact instructions were not followed.

Literal and exact interpretations of what many of my students heard throughout the day often resulted in a very black and white view of the world—the doctor had said “noon” and noon it must be. The schedules they had been taught to follow and rely on from their early years had become a fixed and rigid strategy in their daily lives, one that created a sense of order and predictability. This made them feel safe and prepared, and helped them manage their day. Schedules also serve as a helpful tool for educators and provide structure and a means to prepare students for what lies ahead. Unfortunately, life doesn’t always work that way. An overreliance on schedules without built-in wiggle room to accommodate the unpredictable, as many of us know, can lead to meltdowns.

I definitely needed to figure this out. How could I work with schedules, a proven and effective strategy, while at the same time developing my students’ ability “to be more flexible when things didn’t go according to plan?

The next day, long before noon, I sat the class down for a lesson on time. Now, everyone in the class was an expert on time; I mean, even without a clock in sight, my students had an uncanny ability to know exactly what time it was. It was quite remarkable. So why the lesson on time? Well, I realized that there was still one lesson they hadn’t been taught: ish. Why had it taken me so long to figure this out?

So, I gathered the class around and began our lesson.

“Okay, everyone, today we are going to learn about time. Now, I know you are very good at telling time and following schedules. You are the best. So let’s do some review.”

Holding up both a digital and an analog clock, I pointed to 11:15 and asked, “What time is it?”

“Kenny, yes, it is 11:15.”

“Tally, please turn the hands of the clock to show 11:30,” I continued. “Perfect.”

“Sam, please change the clock to 11:45… Thank you.”

“Ellen, please show us 12 o’clock… Wonderful.”

Pause.

“Now, class, who can show “us 12-ish?”

The class went silent, and then everyone started saying, “Ish, 12-ish” over and over again, giggling with delight at the funny sound and silly time.”

“Well,” I continued, “we all know time markers like o’clock, thirty, half past, noon, and others—but my favourite time marker is ish. Where is it on the clock? Let’s figure it out together…”

I continued, “Let’s look at 12 o’clock. When the clock indicates exactly 12, we can say it is 12 ‘on the dot’ [pause] or we can say it is 12 sharp [pause] or we can say it’s noon [pause] or—[Ellen raises her hand] yes, Ellen, that’s right, we can also say 12 o’clock.” [long pause]

“So, I wonder, does anyone know where 12-ish is on the clock? [pause] Can anyone show us?” Giggles, but no volunteers.

“Twelve-ish can be a little before 12 or a little after 12. It is not ‘on the dot’—it is ‘off the dot.’” I demonstrated ish at several different places on the clock. “It can be a little bit before or a little bit after. It falls in the ish zone.”

I continued: “Today, Ellen will have her eye drops around 12 o’clock, or 12-ish or noon-ish. [pause] Unless we are told ‘on the dot,’ any time can be in the ish zone.”

Again, “the class spontaneously began to chant and laugh, “Noon-ish, ish, ish, noon-ish!”

“So, let’s practice: The school bus will be here at 4 o’clock, but it is raining so it might be a little bit after 4 o’clock or around 4 o’clock. What time will the bus arrive?”

I prompted the class with a hand gesture, and they responded loudly, “4-ish,” still giggling at the this funny ish ending.

For the rest of the week, they adopted ish for every hour of our day. They loved the sound, and the fact that even when “trains, planes, and automobiles” don’t run on time, there is always ish and no more need to panic. We had discovered the “ish zone” and its rightful place on our schedules.

From that day forward, whenever a student became anxious about things not going according to schedule, I simply reminded them of ish and all was well.

As for Ellen, she enjoyed following schedules and making lists, so she was a natural when it came to accurately following recipes. She also enjoyed cooking and baking and was hired by Lemon & Allspice (commongroundco-op.ca/about-lemon-and-allspice), a catering business that uses a co-operative business model, where employees with special needs share in the company’s profits. Developing Ellen’s strengths led to enjoyable work and a sense of satisfaction.

▸ “Don't forget your change!” – Money Math

|

|

When students are anxious, it is difficult for them to focus on school activities and participate in learning. Often, when the social dimension is added to a learning task, it can raise the level of anxiety even more and interfere with learning the new skill. Again, it is not unlike trying to teach a person with a fear of elevators the Pythagorean theorem while riding in an elevator; it just won’t work. I have often found it helpful to separate the social from the cognitive task and combine them only once the new skill has been mastered. This can be useful when preparing students for co-op placements that may require them to interact with the public.

There was a vending machine in the school cafeteria that provided water, soft drinks, and juice. Many of my students had money and often would purchase a drink from the machine rather than buying one from a person in the school cafeteria, as they found it less stressful. However, when I watched them using the machine, I noticed that they often guessed at the amount of coins that were needed for the pur- chase, and if they “got lucky” and a drink was dispensed, they simply took their drink and walked away, not realizing they were owed change. I realized this would be the perfect opportunity to teach them how to conduct money exchanges. Their luck was about to change.

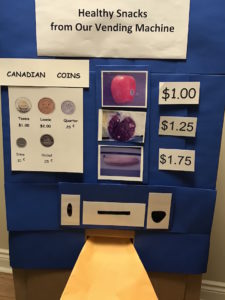

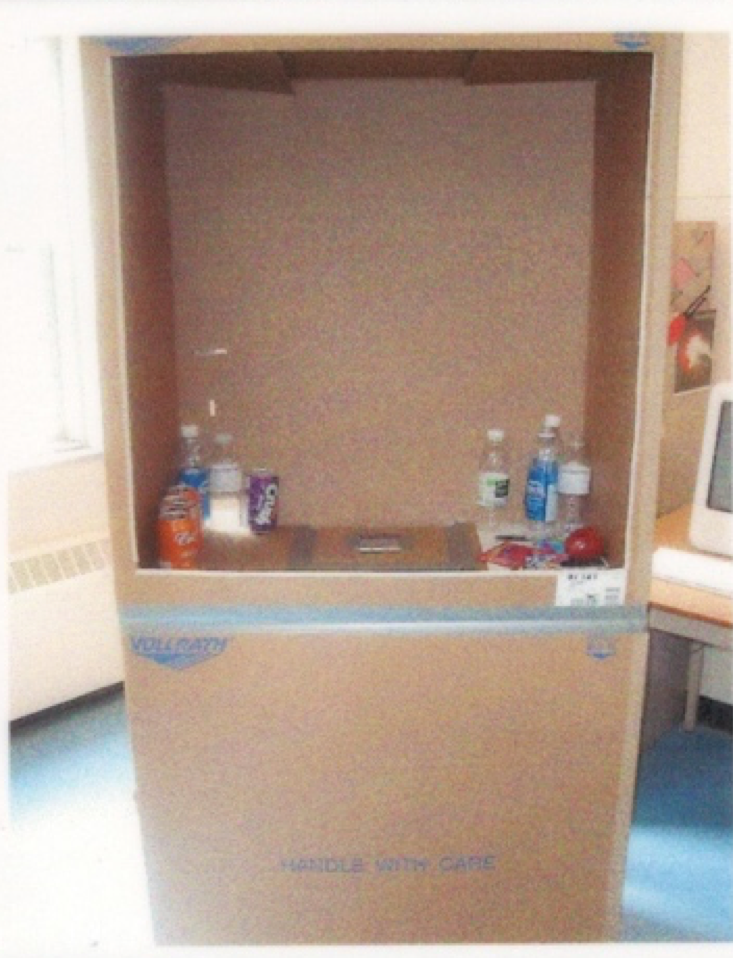

Leaving the human factor out of the equation at first, I would use the vending machine, which they already liked, as a method for teaching math and financial transactions. I ran to the caretaker’s storage locker and found two giant cardboard boxes that would be perfect for designing and building our own classroom vending machine to dispense healthy drinks and snacks. With the help of a handy educa- tional assistant and interested students, we created our very own “human” vending machine, complete with money slot, change chamber, and dispensing chute, as well as an opening at the back where a more capable student would stand hid- den from view to help complete the transaction. The students enjoyed participating in the creation of our classroom vend- ing machine, and this awakened their interest in planning and designing other projects.

The front of the vending machine was designed to be part of a dynamic math lesson for figuring out the amount required to pay for the items listed on the front of the machine. To assist the students in figuring out the proper change, Velcro-backed cards (easily swapped out to match a given student’s level of ability) were placed beside a picture of the item to be purchased, right on the front of the machine. Beside the photo were pictures of coins and calculations, to help the students with their transactions. The cards and calculations were designed incrementally, introducing more difficult transactions as their skills improved. Eventually no tutorial cards would be required. Supplementary pencil and paper exercises, along with games such as Money Bingo, helped the students develop their math skills.

Since the students had varying levels of ability, the more advanced students stood inside the “machine” to check the accuracy of the change. At first, students were expected to use the exact change in order to purchase their item, and only later were they to use coins that would require them to calculate the change they should expect. Sometimes, as is typical in real vending machines, no change appeared (a strategy used to test the students), and they had to say “out of order” or point to the “out of order” sign to indicate that they were waiting for their change. As their skills improved, stu- dents took turns standing inside the machine. It seemed that both receiving and dispensing an item was equally rewarding. When the correct transaction resulted in a drink or a healthy snack, everyone felt like a winner as they cheered together and gave the reminder, “Don’t forget your change!”

▸ Rethinking Eye Contact: Seeing Things Differently

If you want to know what the symptoms of autism mean, you have to go beyond the behavior of the autistic person and into his or her brain. But wait. Isn’t the diagnosis of autism based on behaviors? Isn’t our whole approach to autism a result of what the experience looks like from the outside (the acting self) rather than what the experience feels like from the inside (the thinking self)? Yes. Which is why I believe the time has come to rethink the autistic brain.

–Temple Grandin, The Autistic Brain: Thinking across the Spectrum

At the age of sixteen, Kenny still rarely made eye contact. He was a kind, soft-spoken, and considerate student whose verbal exchanges were purposeful, to the point and delivered in a rather monotone style. He was usually very quiet, except when singing in the community choir, which he still adores—his mellifluous tenor voice was suddenly awakened, transforming his entire being as he discovered a beautiful way to find harmony and connection with the world around him. His singing released emotions buried deep within his heart, now openly revealed with a sense of honesty and vulnerability. A more meaningful connection I cannot imagine.

He had learned to make eye contact when greeting people, but it was just that—contact rather than connection. Nevertheless, his warm and kind nature provided him with a more meaningful way of finding a connection with others, making him a very popular student, well-liked by all. Kenny has sensory sensitivities, and noisy environments can be upsetting, so he would often cover his ears to lessen the impact. He has perfect pitch and enjoyed listening to operas using his headphones.

Kenny was also hyperlexic—that is, he taught himself how to read at a very early age. While he was slow to speak, his reading and speaking abilities appeared suddenly and simultaneously at around age three, as if the written word had been the key he needed to unlock and access the previously elusive world of speech through a different neural pathway, a “road less travelled,” taken perhaps to bypass the confusing sensory world of sight, sound, and dynamic conversational exchanges.

Singing has allowed Kenny to find his true voice and to establish more meaningful connections that extend well beyond our welcoming eyes to a place deep within our hearts.

Even in adolescence, many of my students still demonstrated a level of disinterest with respect to eye contact. The issue was continually being addressed, yet it remained unresolved. And while they had learned to look at us when required, I noticed it wasn’t something they had warmed to. But they had learned to manage and make eye contact when necessary for social reasons, for a co-op placement, or if requested. Other times they might initiate eye contact if they needed your immediate attention. Of course, these are important reasons to be able to make eye contact, but did they feel it helped their own understanding during conversations? I think not. Nevertheless, they were good sports about it and went along with it to please us as they tried to fit in.

So, we have to ask: Does eye contact improve language acquisition skills, speech perception, comprehension, and communication skills for children with ASD in the same way it does for typical children? Or might it actually interfere with language acquisition and comprehension at certain stages of development? Perhaps there is a delicate balance to be found, where we can integrate the individual perceptual, sensory, and neurological challenges faced by children with ASD while helping them understand facial information and body language as they learn to integrate all the moving parts of conversational exchanges. And how do we find the fine balance necessary to integrate all of these diverse skills? I believe these are very important questions that we must ask as part of any therapy or educational program.

What You See Is Not Always What You Get

My adolescent students’ ongoing lack of eye contact led me to believe that there are important neurodevelopmental and sensory issues at play that may result in the “symptom” of what appears to be eye avoidance (Moriuchi, Klin, and Jones 2017). My neuroscientific curiosity, along with my training in psycholinguistics and learning disabilities, made me want to investigate what was behind this lack of or need for eye contact. The research I discovered was fascinating.

Lack of eye contact is often cited as one of the main “behaviours” indicative of ASD. Yet it is actually the absence of a behaviour—that is, something a child is not doing—that arouses so much concern. Many people find the lack of eye contact disconcerting, and often believe (or hope) that correcting it early might ameliorate future difficulties related to personal connections and relationships, communication, and intellectual development. We therefore need to learn as much as possible about the nature of “eye gaze,” in order to determine when and how to best address what lies behind this aspect of autism.

Lack of eye contact often appears during the early stages in a child’s development, as parents are establishing close bonds of love and connection with their child. They soon start to notice the child seeming to evade their gaze or not responding to their name. Parents begin to feel cut off and disconnected from their child, leaving them unsure of where to turn or how to establish a close and meaningful connection. The feelings of loss, alienation, and disconnection can be devastating and the impact on families profound. The “sense” of isolation observed in the child is also deeply felt by every member of the family. And there is that underlying hope that, if eye contact returns, so might the close connection to their child.

But if we find another way of considering “diminished eye looking” (Jones and Klin 2013), we might reach a different understanding and lessen that sense of loss and feeling of hopelessness. What if we consider the child’s change in eye gaze as a response to their sensory environment and perceptual needs? By merely observing the “acting self” without the benefit of comprehending the underlying sensory and perceptual causes that contribute to the development of the symptom, we not only limit our understanding but may also miss out on the opportunity to devise helpful strategies that can address the causes and real language issues revealed by this symptom, rather than simply treating the symptom as a behaviour to be corrected in and of itself.

In other words, by “working with autism” with an appreciation for the sensory and perceptual challenges the child is experiencing, we might gain a deeper understanding of the neurodevelopmental and sensory issues that contribute to the development of the symptom of diminished eye looking. If we see past the outward expression of ASD, we just might discover another way of connecting with the inner life of the child as we continue our efforts to establish a meaningful and caring relationship. For therein lies real hope for realizing a child’s full potential.

Neurotypicals, even many professionals, tend to view lack of eye contact as primarily a socially problematic behaviour, which they believe impedes the development of language, intellectual development, and effective communication. But does it? Or might it be the other way around, with sensory and language problems impeding the development of the ability to manage additional sensory information from facial expressions, eye contact, and body language, which then impacts social development.

First, let’s define what we mean by communication skills. We have non-verbal social communication skills, such as facial expressions and body language, as well as verbal language skills, such as speech perception, language acquisition, and sensory perception/processing, all of which work together during our interactions with people. What role does eye contact play in each of these areas, for both typical children and children with ASD, and how might this influence therapy treatments and teaching methods? For children with ASD and sensory challenges, it is important to not confuse the social aspect of communication with the language processing aspect. Children with ASD may not follow the same sequence of integrative steps and stages in relation to speech perception and language development as typical children do. Therefore, we need to understand more about language acquisition and speech perception, along with the particular neurological and sensory implications associated with the development of these skills for individuals with ASD. (See latest Klin research cited in my book)

ASD is first and foremost a neurodevelopmental exceptionality, which suggests the possibility of an atypical path of perceptual and cognitive development, not unlike that encountered in those with learning disabilities. Developmental delays or differences may result, as more time and practice may be needed at various stages of development in order for these children to experience and integrate all the multisensory modalities of speech perception as one unified sensation (percept). A child may develop their own ways of compensating for their difficulties, and these strategies provide us with valuable insights as we try to figure out the child’s strengths and weaknesses. Educators trained in this type of assessment learn to look beyond presenting behaviours for hidden strengths and abilities. Therapies and remedial techniques that recognize and understand these challenges will require a more nuanced bridging of atypical and typical skill development, along with an awareness of the diverse and varied sensory challenges experienced by each child.

In Teaching Autistic Children, Wing and Elgar describe the children’s behaviour as being closely connected to their sensory and perceptual experiences:

The children behave as if they cannot make sense of the information which comes to them through their senses, especially those of hearing and vision. Their eyes and ears are usually normal. The trouble comes when the information reaches the brain. It seems as if the impression from the outside world cannot be made into a clear and coherent picture but remain a confused and frightening jumble of fleeting impressions. Watching a young autistic child and the way he reacts suggests that sometimes visual impressions and sounds do not get through to him at all, sometimes he is extremely oversensitive and finds light and sound painful and distressing, and sometimes he is completely fascinated by simple sense impressions such as a flickering light or the noise of a friction drive toy.

The children seem to be unable to distinguish the things which are important from those which are trivial. This seems to be closely connected with the difficulty they have in developing an understanding of symbols and abstract ideas, and hence to the poverty of their language development . . . It could be argued that the perceptual problems are primary, but it is equally if not more likely that the lack of ability to use symbols affects the way the children respond to their environment from early life, and that this is the underlying difficulty. The problem will be solved only by careful observation and research, including work with very young autistic children, comparing their development with that of normal babies. (1969, 5)

Perhaps these behaviours can now be seen more as strategies, different “forks in the road” to be followed, which children on the spectrum may develop as a consequence of trying to manage their sensory difficulties while they struggle to process all of the moving parts of human discourse embedded in a sensory environment. But clearly, the desire and wish to understand what is being said is evident if we consider the lack of eye contact through the “eyes” of “the thinking self.” Perception is in the eye of the beholder.

My years of teaching convinced me that sensory issues lie at the heart of ASD, with other challenges emerging as a consequence of this aspect of the child’s neurological make-up. It then becomes a chicken-and-egg dynamic, making it difficult to see the chain of events beyond that which is expressed by the “acting self.” I was also curious about the way my students tried to adapt in light of their receptive language challenges, and instead employed different strategies, more in line with their perceptual strengths but perhaps appearing as odd or strange to typical people.

I’ve also observed which behaviours or strategies individuals on the spectrum develop as a result or consequence of their sensory/perceptual challenges. Once we identify their dominant processing modality, along with the adaptive strategies they have developed on their own, we may be in a better position to design a remedial plan matched to their particular needs and style of learning.

In The Autistic Brain (2013), Temple Grandin wrote about the different types of learning styles, and this important information suggests that we need to take a closer look at what is going on.

So what does the research on speech perception and language processing actually tell us about the way typical people process language, and whether it’s the same or different for individuals on the spectrum? I set about searching for more information about speech perception for both neurotypicals and individuals with ASD and discovered some fascinating research that both surprised and pleased me.

So if we redirect our attention and look a little differently at what is going on, considering a lack of eye contact, as Elgar suggests, “as a healthy attempt to make sense out of a confusion of sensory experience, utilizing whatever skills and knowledge the child has been able to acquire,” we then might ask: Is the child simply eye avoidant, or are they doing something else, something they may need to do as a way of compensating for a deficit or sensory challenge? I tried to listen to what my students were trying to communicate, as they patiently waited for me to figure it out. In my experience, I’ve never met a student who did not want to communicate, and I believe a genuine drive to express needs and wishes is ever-present. Having difficulty communicating is not the same as not wanting to communicate.

Perception Is in the Mind of the Beholder

The brain is locked in total darkness, of course, children, says

the voice. It floats in a clear liquid made inside the skull, never

in the light. And yet the world it constructs in the mind is full

of light. It brims with color and movement. So how, children,

does the brain which lives without a spark of light build for us a

world full of light?

–Anthony Doerr, All the Light We Cannot See

So what is perception? It seems that what we end up seeing and hearing (i.e., perceiving) has more to do with the brain/mind and less to do with the eyes/ears. To understand perception and how we experience the world, we must look past the “acting self ” and search for the answers within the “thinking self,” for there is still so much to be uncovered. Different sensory experiences and perceptions, far from being meaningless, tell us much about the inner workings of the mind, and that is where we just might find what is really going on. Some children may focus on reading lips rather than looking at the eyes to help them with speech perception. Other children may turn their head with an ear toward the speaker, when having difficulty integrating sight and sound. What may appear as a lack of social connection may actually be an attempt to process what is being said.

Exceptional Minds takes a closer look at these questions and brings together research from various disciplines to help shed some light on this new understanding of the autism spectrum.

▸ Now You See It, Now You Don't – The Figure-Ground Dynamic

We can’t possibly manage all of the information coming our way during our daily lives without feeling overwhelmed. We just need to see the “big picture” and focus on the details only when necessary. In this context the whole is greater than the parts as we go about our daily lives. But our perceptions and focus can change depending on the task at hand and learning to efficiently manage the details (the figures) as well as the big picture (the figures in relation to the ground) can be both a strength and a weakness, depending on the context. This juggling of perception and focus is dynamic in nature but may present a challenge to some individuals on the spectrum. This skill is not unlike the depth-of-field function in an SLR camera, which can change the focus to suit the purpose or artistic sensibility of the user.

The invisible gorilla illusion described in the fascinating book co-authored in 2010 by Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons, The Invisible Gorilla and Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us, highlights the interesting influence of the figure/ground dynamic and the different ways individuals perceive the world.

Asked to count the basketballs being rapidly passed between players during a practice, many viewers fail to notice the person dressed in the gorilla suit who also appears on the court; their focus on counting the balls seems to make the “gorilla” invisible during this task.

Do such illusions help or impede our understanding of the world? Are they simply interesting parlour tricks or are they something more? Are perceptions exact representations of all that is before us, or, more likely, are they “good enough” representations of our environment, allowing us to accomplish tasks as we navigate our way through our dynamic, fast-paced world? Is “what we see” more accurately expressed as “what we perceive”—as we learn through experience which information is relevant and which can be ignored, filtering out what is extraneous and might otherwise interfere with our ability to handle all the information around us? Does the end justify the less accurate means? The dancing gorilla disappears or reappears depending on the task the brain wishes to accomplish.

You can experience the invisible gorilla illusion yourself on the website of Daniel Simons, head of the Visual Cognition Laboratory at the University of Illinois. His TEDx talk, “Seeing the World as It Isn’t,” is also worth a watch—you can find it on the same page. dansimons.com/videos.html

Perception is in the Mind of the Beholder

Our perceptions and what we perceive seem to be matched to the task we need to perform. They need to adapt when presented with different purposes, sometimes seeing the forest and sometimes just the trees; sometimes the basketballs and sometimes the gorilla. Too rigid a focus may result in misperceptions that could compromise our ability to adapt, for we need to move back and forth between figure and ground as the task demands.

Sometimes too accurate a focus, based on fine details, can take hold and interfere with the ability to take in the bigger picture. At the same time, an “eye for fine detail” and a more narrow focus can also be considered a strength and may lead to career opportunities. It is not either/or, but both/and. So how do we develop the ability to move back and forth within this figure/ground dynamic? Do some individuals on the spectrum struggle when trying to shift their focus in figure/ground situations? How do we encourage the use of both skills without sacrificing special abilities in the process?

The experience of N.S., a young man with an extraordinary ability for seeing fine detail and detecting patterns, captures the challenge of recognizing this ability as a strength and as an opportunity to address the social costs that may accompany such abilities. To see his skill as simply quirky and odd, or as antisocial behaviour, would serve only to further isolate a very engaging individual. Thankfully, his strengths were recognized, resulting in a more positive social experience, as described in a story on the online news magazine Forward:

A few years ago N.S., who has autism, thought the Israel Defense Forces wouldn’t take him . . . N.S. . . . spent his childhood in mainstream classroom settings, where he had focused on studying film and Arabic, but expected to miss out on being drafted—a mandatory rite of passage for most Israeli 18-year-olds. Now, more than a year into his army service, N.S. is a colonel who spends eight hours a day doing what few other soldiers can: using his exceptional attention to detail and intense focus to analyze visual data ahead of missions. Soldiers with autism can excel at this work because they are often adept at detecting patterns and maintaining focus for long periods of time. “It gave me the opportunity to go into the army in a significant position where I feel that I’m contributing,” he said.

(Sales 2015)

Recognizing his strengths also gave N.S. the chance to develop his weaker social skills alongside his strong attention to detail, in the company of others with common interests and goals, each enhancing the other.

While it is understandable that many children appear frustrated by their sensory and perceptual challenges, or find social situations to be challenging, we should view their frustration as more of a consequence of their challenges, rather than as simply a symptom of ASD or an unwillingness to socialize with others. The children have had to adjust to their sensory challenges on their own by developing adaptive and compensatory skills that may appear on the surface to be unusual “behaviours.”

Having difficulty with communication and not wanting to communicate should not be viewed as one and the same. As yet, I have not met a student who did not display the need or desire to express themselves and be understood. Everyone has something to contribute; everyone belongs. N.S. was finally accepted for who he was and felt that he was contributing and valued.

▸ SPECial TRaits of Unique Minds – Understanding the SPECTRUM

“The key to autism is the key to the nature of human life . . . The reward for the effort involved is a deeper understanding of human social interaction and an appreciation of the wonder of child development.”

–Lorna Wing

Our current view of autism as part of a broad and multidimensional spectrum of traits can be traced back to 1979, when British child psychiatrist Lorna Wing and her colleague, psychologist Judith Gould, first introduced this new and revolutionary understanding of autism. Over the course of their research, they came to realize that it was the children who didn’t fit into neat little categories who offered the greatest insights and would help them develop the concept, which was more like a spectrum. As a result, they placed less emphasis on “giving a name to the condition” than on “identifying all the needs a person has” and, by association, the supports that would help them reach their potential (Ayris 2013, 33). Lorna Wing was always cautious about diagnostic labels, seeing them as useful only for getting people the services they needed. She was often quoted as saying, “You cannot separate into those ‘with’ and ‘without’ traits as they are so scattered . . .” (Rhodes 2011) and “We need to see each child as an individual” (Telegraph 2014).

Almost forty years after its introduction, the concept of an expanded autism spectrum was finally added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) in 2013—a tribute to Wing and Gould’s foresight and wisdom as we continue to move closer to understanding the complexities and the hidden potential of the human mind and brain.

Wing and Gould first described their view of autism as a broad and diverse continuum. They later revised it, describing it as a spectrum disorder, reflecting a more nuanced and dimensional understanding. As Gould (Feinstein 2010, 153) explained, “We first called it the ‘autistic continuum’ and then we realized that the word continuum had an implication of discrete descriptions along a line, whereas that was not what it really was. It was not a question of moving in severity from very severe to mild. That was not what we were trying to get across. The concept of a spectrum is more like a spectrum of light, with blurring.”

My book, Exceptional Minds across the Autism Spectrum, is dedicated to developing an expanded understanding of the autism spectrum in all its forms and aspects. Today, the concept of an autism spectrum may help redirect our focus from the label to the individual and their needs. As we continue to broaden our understanding of “thinking across the spectrum” and beyond, we can begin to achieve a deeper appreciation for the wonder of child development and the potential to learn and thrive.

▸ Echolalia – Marc: “And Me without My Camera”

One of the best compliments I have ever received was from a student who loved The Simpsons. I had an important meeting at school that day, so I arrived in the morning wearing a nice dress with a lovely batik scarf, instead of my more casual, everyday look. I really didn’t think my students would take much notice, but as I entered the class, Marc immediately ran over to me and, in his best Bart Simpson voice, said, “And me without my camera.” A better compliment I couldn’t imagine. It still makes me smile and blush a little even as I write about it.

Now, this exchange on its own may not seem that unusual, but keep in mind that this same student had a great deal of difficulty participating in the more traditional prosaic and spontaneous conversational exchanges of daily life, the sort of exchanges most people take for granted. Instead, Marc frequently relied on his cherished “scripts” to express himself and often had difficulty finding his own “voice” and spontaneous words. Many professionals in the field of ASD refer to this style of speaking as echolalia. And many still view it as a meaningless parroting behaviour that should be discouraged. But the research presents a very different understanding of this trait.

Conversational exchanges require quick responses and improvisation. For most people, such exchanges happen quite naturally and spontaneously, a daily occurrence that we find neither onerous nor challenging.

Yet, we marvel at jazz musicians who can create original and immediate musical responses and improvise in the moment, a skill that eludes many classically trained musicians. Imagine a classically trained musician, reliant on sheet music and following the conductor’s lead, suddenly asked to “Take it!” and play a jazz riff to Beethoven’s Ninth; this would certainly present a daunting challenge to even the most experienced classical musician. For many people with ASD, the spontaneous and improvisational nature of conversational exchanges in daily life demands skills not unlike those of jazz musicians.

I believe my students who sometimes relied on “scripts” and borrowed dialogue used their personal databases of memorized scripts to keep pace with the rhythm of language and to quickly fill the silences that might otherwise have brought conversations to an abrupt end. Their method and style of engagement may have appeared rather unconventional, but the desire to connect with others and communicate was nevertheless strong and sincere, and their unique method of communicating was often delivered with confidence, good humour, and a sense of accomplishment. They seemed pleased when they found the right quote to match the situation. “And me without my camera” was a perfect match, wouldn’t you agree?

Although many of these students had well-developed vocabularies and verbal abilities, they still found themselves at a loss for words during more prosaic and fact-based exchanges. (I encountered many students over the years with similar learning profiles, who also spoke and understood several other languages.) At such times, their style remained short and to the point. However, when they wished to express a feeling or talk about a passionate interest, their style became more animated and was often peppered with borrowed dialogue. And when they wished to participate and be part of the action in the classroom, they quickly found a fitting phrase to match the situation as a way to join in. My other students who did not share this trait willingly followed suit and would play the “speaking in scripts” game as a starting point for mutual connection. The scripts seemed to provide a way for the students to break the ice, since initiating conversations in more conventional ways presented a more daunting prospect.

In more stressful situations, I also noticed a tendency toward the use of immediate echolalia—that is, repeating or “echoing” what is just heard. Their repetition of what they heard would become more pronounced and repetitive, not unlike what individuals who stutter experience. But instead of a letter or syllable being repeated, as is the case with stuttering, entire phrases would get caught up in a loop of repetition from which they seemed to have difficulty breaking free. We understand the stutterers’ challenge and do not regard this trait as odd or meaningless, but do we extend the same understanding to individuals with ASD? While at times we may have difficulty comprehending what they are trying to say, there is no mistaking the meaning behind their words: their anxiety. For me, that came through loud and clear as I observed my students’ struggles with expressive communication.

Many of my adolescent students, including Marc, attended a weekly community centre “dinner and dance” program with other young adults. I was curious to see what my students were like outside of the school setting; I thought it might give me the opportunity to broaden my perspective and deepen my understanding of their lives beyond the classroom walls. So one evening, I went along to observe.

The dance instructor routinely began the evening program by asking all the participants to form a circle and introduce themselves. Newcomers were asked to go first. I noticed that Marc was becoming rather anxious as his turn to introduce himself to the group approached. Marc was uncomfortable in large group settings, and although he had participated in the introductory circle before, he was beginning to show signs of stress and anxiety. Larry, his good friend and classmate, was standing right beside him and, when it was his turn, said with confidence, “Hi, my name is Larry.” Marc knew that he was next, and he began to frantically pull on the threads of his shirt. Then, he yelled, “Hi, my name is Larry.”

Now, Marc was very capable of introducing himself correctly, and of course he knew his own name, but under pressure, like a deer caught in the headlights, he resorted to an old “behaviour,” long since outgrown, of repeating what he had just heard. Over the years, I noticed that many of my adolescent students with ASD sometimes fell back on old childhood strategies or behaviours that were no longer in evidence but suddenly resurfaced as a way of coping with new and unfamiliar situations. This is a very natural human reaction we’ve all experienced in one form or another. Old habits die hard.

What’s Your Favourite Colour?

The tendency to copy others when under pressure is not as unusual as it may seem. Marc’s experience at the community centre immediately reminded me of a scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in which we find the Knights of the Round Table preparing to cross the Bridge of Death, with each knight required to answer three questions before being allowed safe passage.

I don’t want to give too much away, in case you haven’t viewed the scene, but we find ourselves laughing at the knights as they try to answer “the questions three,” for we recognize ourselves and can appreciate why the knights who are awaiting their turn pay extra-close attention to the correct answers already offered by Lancelot, who was allowed to safely cross the bridge. Everyone, at one time or another, has relied on copying what they’ve overheard in order to get out of a tricky situation, to process what has been said, or to buy time as they try to think of an answer. But in this scene, copying what is heard actually proves fatal.

I love this sketch, especially the clever bit at the very end, for it not only pokes fun at this normal aspect of human nature, but also goes further, providing us with an even deeper appreciation for King Arthur’s special interests and attention to facts and details. King Arthur, as portrayed by the Monty Python actor, is what Temple Grandin (2013, 187) would call a “word-fact thinker,” and his special interests result in a surprising and triumphant outcome. By highlighting the value and benefits of King Arthur’s special interests and attention to fine detail and facts, the scene allows us to laugh and then pause and appreciate the extraordinary nature of individuals with keen interests and passions.

You can view the “Bridge of Death” scene, and have a good laugh along with a good dose of insight, on YouTube. Perhaps King Arthur and his knights belong somewhere along the spectrum. I’d like to think so. youtube.com/watch?v=Wpx6XnankZ8

▸ COVID-19: Staying Apart, Learning Together

There’s a world to discover at our fingertips.

During these challenging times, many parents suddenly find themselves looking for resources and supports to keep their children engaged and connected. This can be an even greater concern for parents with special needs children. As a special educator, I want to reassure parents that many valuable learning experiences and opportunities to connect with others can still be realized from home. And with the increased level of anxiety being experienced by many family members, it is important to take the time to have fun with your children. Work on family projects, pursue interests or (new) hobbies and discover many valuable life lessons as we all explore the challenges ahead. I wish you much success.

The following resources can be enjoyed by all children and their families.

Here’s a free pass to countless museums:

1. Ripley’s Aquariums At Home – virtual tours, educational materials, and crafts

Take a virtual tour with online activities. Visit: https://www.ripleyaquariums.com

2. Visit the Art Gallery of Ontario – In response to COVID -19, the gallery has launched AGO from Home. Enjoy online collections, videos and DIY and How-To videos (home schooling). https://ago.ca then click on Experience the AGO

3. Canada Science and Technology Museum https://ingeniumcanada.org

The Railway Collection looks very interesting. Explore the site for more gems. Visit virtual programs like the The Science of Sports with hands-on activities and online experiments (school-based activities for all ages).

4. Tate Art Gallery https://www.tate.org.uk/kids This is one of my favourites, so engaging and beautifully presented. Check out the menu headings – Make, Games and Quizzes, and Explore.

5. NASA Langley Research Center https://www.nasa.gov Excellent lessons for students. Although we must stay at home this site allows us to visit the far reaches of outer space and the wondrous world of science.

6. Lots to explore at https://kids.nationalgeographic.com

7. Visit Google Earth and check out the Editor’s Picks. From Celebrating Harry Potter to deep sea exploration, with Jill Heinerth in Dive into the Planet, Canadian Geographic. There’s much to learn from your google guides. Try https://earth.google.com and/or (Using Chrome) https://earth.google.com/web/@0,0,0a,22251752.77375655d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=CgQSAggB?hl=en

Also visit the sites fascinating education resources for all ages:

https://www.google.com/intl/en_ca/earth/education/resources/ Check out We’re Talkin’ Baseball, and Evidence on Earth – Science in the Natural World.

8. Singing together is another way to connect with others. Join an online choir by visiting https://www.choirchoirchoir.com. The entire family can join in singing your favourite song. You can an even make home-made instruments, shakers, pots/garbage cans turned into drums… just use your imagination.

9. Time for a break from each other. Invite grandparents, family and friends to connect with your child online by reading a story, playing a game of cards or sharing a favourite activity.

10. For more school-based interests visit the free Khan Academy

https://www.khanacademy.org

And check out the free resources from Scholastic publishers as part of their generous response to help families during the Corona outbreak.

https://classroommagazines.scholastic.com/support/learnathome.html

See the Learn at Home hub for families and educators. Thank you Scholastic.

Podcasts & Interviews

Hear Corinne speak about teaching exceptional minds on the following podcasts. New episodes will be added as they appear!

Live Seminars

Live seminars with Corinne archived here. New seminars and talks will be added as they appear!

Listen Now:

An archive of newsletters. Be sure to join the newsletter to keep up with the latest about Exceptional Minds.

▸ From Acceptance to Action – SPRING 2022

Autism At Work

For me, April is a time to celebrate the accomplishments of the autistic community by recognizing the importance of sharing stories of success so others will benefit. I will introduce you to individuals from Canada, the US and the UK who have much to teach us about increasing and improving opportunities for meaningful employment and civic engagement, with a real sense of belonging and contributing so everyone benefits.

In Canada:

Common Ground – Lemon and Allspice Cookery: Self-ownership for people with disabilities.

Carolyn Lemon and her daughter Cathy’s “recipe for independent living” is both inspiring and delicious.

Visit their cookery by clicking here.

Meet Brad who can build anything. With help from his dad, he started his own furniture assembly business, madebybrad.com

Watch Brad at work both at home and on the job. Click here.

Goodfoot is off to a good start. I use their courier service and am most impressed. I think you will be too. Check out their videos here.

Spectrumworks job fair will take place soon on April 8th and is now a virtual event.

You can learn more about the event at the links below and check out the exciting newsclip filmed a few years ago:

Spectrumworks job fair

News clip

In the United States:

Jeremy’s Vision: Meet a talented artist in his studio. Click here

Jeremy’s mother Chantal has written many popular books about autism. Learn more

Meet accomplished children’s author, eco-artist and autism advocate JIGSAW Grant. Click here

Visit Temple Grandin on the job as she discusses the importance of encouraging children to take on responsibilities outside the home in preparation for future employment as autistic adults. Click here

Visit careerpathways.org. Founder Maisie Soetantyo interviews a diverse group of autistic individuals working at various jobs they love.

Visit autismgrownup.com. Dr. Tara Ragan provides excellent online resources.

In the UK:

The Autism Advantage in the Workplace. In this youtube video, Adam Feinstein, author and autism advocate, introduces us to a diverse group of individuals who are using their strengths to find meaningful employment, including individuals like Feinstein’s son Johnny who have limited speaking ability. Their stories are described in Feinstein’s latest book, Autism Works, and this talk celebrates their abilities and interests, and the important employment opportunities that are out there. Feinstein emphasizes the need to continue to dispel many misconceptions surrounding autism and the world of work. This talk runs 50ish minutes but is worth watching when you get a chance. Click here

Let’s keep working together to bring about meaningful change.

▸ Inspiration and Celebration – WINTER 2022

Wishing you all a new year of resilience, good health, and joy in pursuing your dreams. I want to begin by celebrating the achievements realized during the past few years by people who continue to face obstacles beyond the challenges of COVID. Living with uncertainty has meant we all have learned to adapt during these unpredictable times. Yet for people with disabilities or developmental differences this remains a familiar and ongoing challenge. At a time when it’s easy to feel discouraged, it sometimes helps to take inspiration from those who have managed to find a path forward in ways we couldn’t even imagine. Let’s continue to adapt together long after this pandemic runs out of steam so that no one is left behind.

Let’s begin by meeting some amazing people. First, I’d like to introduce you to the VIVA Singers. I was invited to one of their concerts several years ago by some of my students and the next thing I knew I was signed up as a member. They not only helped me discover my voice but also opened my eyes and ears to the beautiful and inclusive world of music. Then COVID came along and almost silenced our voices. But our choir was well versed in dealing with obstacles and found another way to carry on as a community. If I Had A Hammer along with the magic of technology capture that determined spirit quite well as I’m sure you’ll agree after watching the performance. Also, check out VIVA’s message below to learn more. New members are always welcome. Next, I’d like you to meet the talented artist and author Rita Winkler who recently published her beautiful book, My Art My World. Be sure to visit her website for tips on creating your own works of art. Then, take a listen to a new and original release from the ASD Band and join in and celebrate their powerful and upbeat message. And then there’s Gabriel who will share his important message about inclusion. Gabriel also sings the praises of Jake’s online jam sessions where he enjoys performing his favourite songs. I was invited to join this wonderful musical get together during COVID and I’ve never looked back. If you’d like to learn more and even join in, just click the link below. Finally, you’ll get to enjoy the inspiring Shalva band, the Jerusalem Symphony, Tareq Al Menhali and Arqam as they perform A Bridge over Troubled Waters, setting us up for better days ahead.

A fresh and inspiring start to the new year is just a click away:

Viva Singers, If I Had A Hammer

▸ Back to School in Uncertain Times… – FALL 2021

In my long career in education, I’ve witnessed an ongoing resistance to change and to adopting new and innovative approaches to learning. But the pandemic has forced change upon us and can be viewed as an opportunity to seize this moment and run with it. The current educational challenges have made educators more acutely aware of the different learning styles experienced by students. And that is a good thing.

As we head back to the classroom either virtually or in-person, new and unknown challenges are adding further concerns to an already difficult situation. Yet there is hope for better days ahead and an opportunity to reimagine a better school experience for all children.

What the pandemic experience has taught us:

- It has forced our schools to finally recognize many of the inequities that have been ignored or overlooked for far too long.

- It has challenged our schools to create innovative ways to address those shortcomings and recognize how much more needs to be done.

- It has opened up the lines of communication between schools and families, establishing a deeper appreciation and respect for the challenges they each face. This new understanding holds great promise for a more meaningful partnership going forward.

- It has shone a light on the important role parents can and should play in shaping and reimagining a better school experience.

- The pandemic has forced us all to pivot and adapt very quickly, demonstrating change for the better is possible. While many problems remain, they can no longer be ignored. This is just the beginning as we prepare to meet the next set of challenges.

Here are a few useful and practical links to free resources and professional advice to help get us started:

1. IRCA Indiana Resource Center for Autism: Their RETURNING TO SCHOOL resource materials provide valuable information and strategies for parents and teachers. I really like the form, Information About My Son/Daughter on the Autism Spectrum. This brief form will help parents provide important information to better prepare their child’s teachers. Click here

2. NAS National Autistic Society, Welcome to Autism Practice-Education. Sign up for their newsletters or check out their popular website for information about your particular area of interest.Click here

3. In case you missed it, checkout the Resource section of my website for learning strategies, free excerpts from my book, newsletter ideas (like the Winter/21 edition), podcasts and my Youtube book presentation: Click here

It is my hope that we can create a school culture based on dignity, respect, social inclusion, and the right to a meaningful education for each and every deserving student.

▸ A Time to Stop and Smell the Roses… – SUMMER 2021

At last summer is here. After a difficult and challenging school year it is time to put the 3Rs aside and replace them with the important 3Rs of summer…Relax, Reflect, and Rejuvenate.

Thankfully we are now at a place where we can get together with family and friends as COVID restrictions ease. Let’s take full advantage of reconnecting and have good old-fashioned fun. Our children need these connections more than ever and so do we. Let’s try to put the worries about the school year behind as we transition to the lazy days of summer. In that spirit I will keep this newsletter short and encourage you to reconnect with what was truly lost this year. Community life can restore us and help ground our children. Seek out understanding and supportive friends as our children rekindle their relationships. And remember, “don’t worry be happy” as one of my students often sang to me when I looked too serious.

So, think about sitting down with your family and coming up with a list of the things you really missed during COVID and together put this plan into action. Recharge your solar batteries, enjoy your favourite ice cream, cool off at a splash pad or pool, and rediscover your resilience.